When “Say Lolly” Doesn’t Work

“Say lolly or I won’t give you lolly”. How many times do you find yourself saying this sentence? As parents with a child with a severe language and speech impairment we often try to elicit our child’s speech by asking them to say the word before giving them their favourite food or toy. How many of us have stopped to reflect and wonder “Does this strategy really work?”

Let us have a look at what the research says.

High pressure situations can have a negative impact on motor performance in both adults and children across a variety of tasks, including speaking (Beuter & Duda, 1985).

Higher pressure techniques, such as direct request for imitation (“say ball”) do not enhance word learning outside the treatment setting to any greater extent than lower-pressure strategies, such as modelling “you want BALL, the big BALL”. This is because high-pressure situations can have a negative impact on motor performance across speaking tasks. High pressure techniques also include “test questions” within play; for example, asking many questions to test the knowledge of the child or to try to interact with him.

How can we elicit the child’s vocalisation?

Listed below are some low-pressure strategies that we can increase verbal imitation and spontaneous use of language on a daily base.

Imitating the child

If you want to be imitated, imitate first. Imitating the child serves to model the skill of imitation itself. Studies (Field, Field, Sanders and Nadel,2001) found that when parents imitate their children’s behaviour, including vocalisations, on a frequent basis, spontaneous imitative behaviour increases in their children’s speech as well. Imitation is a skill that can be learnt. To increase the imitation skill in your child, respond as if your child’s sounds are words: repeat them, answer them, or say a word that is similar to the sound and that makes sense in context. For instance, if the child says “ba”, a mother might respond “Ball” or “bottle”, depending what is in the context. If the child vocalises often “ma,ma”, the mother might respond “ma,ma, my turn” when playing with toys. Or, the child says, “mama” when looking at family pictures. This imitation model and then recasting will be facilitating the creation of a “mini conversation” by making one of the sounds the child makes, waiting for your child to respond, and answer back with the same or a different sound.

Augmentative and alternative communication (AAC )

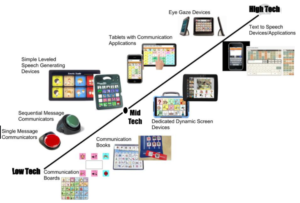

AAC include the use of manual signs, gestures, pictures, photos, videos, written words, communication boards, high tech electronic devices.

Providing access to Augmentative and Alternative Communication (AAC) gives a great support to a child who has substantial speech language difficulties as it facilitates social interactions and speech development. A review of six studies regarding the impact of AAC on speech language development in children with disabilities, demonstrated that 89% of the participants showed increases in speech production with the commencement of the AAC (De Thorne et al, 2009).

The implementation of AAC can involve manual signs that can be modelled at the beginning hand over hand, such as “more” when a child is reaching for another piece of toy or food, or “open” when a child is struggling to open a container.

For children experiencing difficulties coordinating manual communication, an AAC device with “core vocabulary” book can be created, where pictures or symbols of favourite objects, people, and activities are included. Another alternative can be to put the picture of the food items on the refrigerator so the child can point to the picture he wants. The child can also be trained to give the picture of the item he or she wants in your hand, following the hierarchy of Picture Exchange Communication System (PECS). PECS (low tech AAC) promotes an acquired, self-initiating and functional communication in children with development disabilities and autism (Bondy AS, Frost LA,1998)

Tactile and Proprioceptive Feedback

Source: miraclesincommunication.com

What happens if your child cannot imitate a new word or sound yet? In this case, we will need to focus on the sensory feedback which plays an essential role in establishing new speech behaviours and guiding new movements within their motor system. For this purpose, multisensory strategies (visual, tactile, proprioceptive input) have been provided to teach children the movement sequences of speech.

Children who experience severe speech difficulties, such as Apraxia Childhood of Speech, may not have the internal feedback that make them review and correct their attempt to say a specific word. Thus, every attempt will be like the first attempt. For this reason, it is important to provide an augmented external feedback to these children in order to facilitate speech production skills and to build a motor memory of a correct model for the articulation goal.

Tactile and Proprioceptive Feedback have been used by the PROMPT method (Restructuring Oral Muscular Phonetic Targets). This treatment uses tactile prompt, such as touch or pressure, to the child’s face for each English phoneme in conjunction with auditory and visual models (as the therapist repeats the target word while providing the tactile input to the child), to cue the child for the correct production. In the PROMPT approach, the motor system is the result of coordinated actions between and among all the individual’s domains (Physical Sensory, Cognitive Linguistic and Social-Emotional) and the external influences from the environment. Therefore, it is important that the clinician looks across all the domains to find ways in which to utilise the client’s strengths to increase his or her verbal communication.

For instance, if the child shows atypical tone, muscular development delay or difficulties with sensory system, the intervention will be including appropriate levels of activity (to increase or decrease the child’s arousal), postural activation and supported seating.

On the other hand, if the child ‘s muscular, motor, and sensory system is adequate, the treatment to focus on is to increase the child’s imitation, memory and receptive while targeting specific motor movement (mandibular control, labial/facial control, lingual control and sequenced movements). The goal will be to link auditory, tactile, visual, and motor prompt within the social routine to bring awareness to the concept of the word without the child’s need to repeat the word that we are targeting on.

For example, if the child is very motivated by bubbles, depending on his or her movement goals, the words that we can prompt with a tactile feedback are: Pop, “Bo”/ Blow, “Ah dah” /All done, “Dah”/ Down, Me, “Mo” /More.

Exaggerated intonation, verbal routines, and pauses

The literature shows that speech production is facilitated by exaggerated prosody, slowed timing and addition of melodic line (Waide,1996). These findings can be applied in our daily speech during social routines with our children. For example, we can exaggerate our speech prosody while we do some movements with the child by saying “Uuuuup….and doooown”. By repeating at least five times these routines over the week, we can insert afterwards a pause after “Up” so the child needs to complete the anticipated word “down”. When the child is bouncing on a big ball, we can model “1,2, 3,…….bounce” and repeat it a few times after we can stop after 3 and pause to give some space for the child to communicate with us. The same technique can be used to finish activities by saying “Alllll….done” or during everyday routines “Light…………..on” or during songs “ Twinkle, Twinkle, Little……….Star”. This explains that songs and routines that have a predictable rhythm are a highly effective tool to increase verbal as much as pre-social skills, such as attention to the adult’s face. It is important to keep the number of words you are working on very small but being consistent with those target words. At the beginning, therapists want to reinforce the child’s expressive initiation; therefore, speech approximation of the target word still indicates that the child has a representation of the word, even though it does not sound exactly like an adult production (S. Rogers,2010)

For any questions regarding these techniques, please don’t hesitate to contact our therapists to learn more.

References

Beuter, A., & Duda, J. L. (1985). Analysis of the arousal/motor performance relationship in children using movement kinematics. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 7(3), 229-243.

Bondy AS, Frost LA. The picture exchange communication system. Semin Speech Lang. 1998;19(4):373-88; quiz 389; 424. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1064055. PMID: 9857393.

Dale, P. S., & Hayden, D. A. (2013). Treating speech subsystems in childhood apraxia of speech with tactual input: The PROMPT approach.

DeThorne, L. S., Johnson, C. J., Walder, L., & Mahurin-Smith, J. (2009). When “Simon Says” Doesn’t Work: Alternatives to Imitation for Facilitating Early Speech Development. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 18(2), 133. doi:10.1044/1058-0360(2008/07-0090)

Field T, Field T, Sanders C, Nadel J. Children with Autism Display more Social Behaviors after Repeated Imitation Sessions. Autism. 2001;5(3):317-323. doi:10.1177/1362361301005003008

Rogers, Sally J., G. Dawson. Early Start Denver Model for young children with autism: promoting language, learning, and engagement, 2010. The Guilford Press, New York.

Ilaria holds a Bachelor Degree Honours in Speech Pathology and she is a fully registered as a Speech Pathologist in Italy. She is completing a research project partnering with The University of Sydney in Childhood Apraxia of Speech, a motor speech disorder affecting children’s ability to program and plan oral muscles in order to elicit speech sounds. She has presented work in conferences in Italy (AIDEE Conference), USA (Motor speech Conference) and Australia (Speech Pathology Australia Conference).